During earlier times in the Cordillera highlands of Ifugao, there were no

playgrounds and parks where children could spend their leisure time

playing. There were no roads, bridges and

schools then. Only trails, the “payo”

(rice fields) and “habal” (slash and burn agriculture) and the wilderness that

are basic institutions for learning the basics of life.

Mun

ba’nong

Ha’bal or slash and burn agriculture

mun'a'ladu

The space under the native house called “da-ulon” and the adjacent areas

surrounding the house called “aldat-tan” are basically the first known playpen

for children of all ages. The numerous

intersecting trails that lead to the vast wilderness serve as the extension for

learning basic skills.

al’dat’tan

al’dat’tan

Early

Ifugao children have the “yok-ka” which is equivalent to the present day

“children’s swing seat”. “yok-ka” is a

“tuwali” word for swinging to and fro in any suspended object, usually a vine

or a “lituku” (rattan palm) clinging to a tree. The player hangs and grasps firmly the

suspended object with both hands, and from an elevated platform, pushes himself

forward. The player, after reaching the

end of the pendulum, returns to the starting point. The cycle goes on until external interference

or drag brings it to a halt.

Children

always find leisure in catching dragon flies with the use of bird lime or

“pu’-kot”. With the use of a bolo

(o’tak), a cut away is made on the bark of a jack fruit (ka’kaw) enabling the

white sap to come out and become sticky.

The sticky residue which is the “pu’-kot” is gathered (litigon) by use

of twigs or coconut midrib (ba-ing). The

“ba-ing” or twig with the “pu’-kot” on it is placed on the end of a mountain

red (bi’la’u’) allowing a farther reach to the unsuspecting dragonfly Out in the grassy area or rice paddy dikes,

children go out to catch dragon flies.

Dragon

flies are categorized in the “tuwali”

dialect as follows: “du’-u’-ti – small grey dragon flies; “bal-la-hang” – red

and yellow colored dragon flies; “bug-gan” – orange colored dragon flies that

stays stationary in midair for an indefinite time; the “bon-ngot” – medium size

grey dragon flies and “bang’gu’luwan” the biggest giant dragon flies. Children do not bother the strange looking

damselflies that are found in springs with the belief that they are pets of

unseen spirits and deities.

Older

children who baby sits (mun’a’dug) their younger siblings are also engaged in other

leisure. The “pan’ni’til” will be one of

the numerous “traditional games” that is fitted for a “mun’a’dug”. “Pan’ni’til”

is the “tuwali” word for entangle. The

game makes use of the flower of an endemic grass about two to three feet

tall. The flower looks like a round small

lollipop which is a few centimeters in diameter. It has a peduncle which is about one to three

inches long. It is green in color but becomes dull gray to

black when mature. This grass grows

abundantly in the “aldat’tan”. It is the

flower that the children would gather to play the “pan’ni’til”. The playing pair, holding the flower by the

peduncle, entangles and locks the lollipop like heads and pull. One of the flowers’ head would sever and

fall. One flower after another replaces

the looser as the game continues. Some

children uses the “o’ban” in securing their subjects. The “o’ban” is a blanket

or cloth that is used to strap or secure a baby in the care giver’s body. The baby could be placed either in front or

at the back.

Entangled lollipop look alike flowers for the pan’ni’til

game

These

are the three common beetles in the highlands of Ifugao that children play with. The “abal-abal” or “salagubang in low lands;

the “ang’gi’giya”, brown beetle that

lives underground and a metallic black or green colored beetle that children call “ling’nga’ling”. The “abal’abal” is gathered by shaking tree

branches. The “ang’gi’giya” is dug on

the soft soil under tree trunks and banana plants and the rare “ling’nga’ling”

is caught when it flies near you. To

play with these beetles, a string or thread is tied to the hind legs and let

the insect fly while the child secures the string. Children would also let the beetles engage

in a pushing or pulling matches. The

wings are locked at the end of a bamboo stick with splits. Beetles locked facing each other would go for

a pushing match while locked opposite each other would go for a pulling match.

Abal’abal ling’nga’ling

During

those earlier days, children copied from low land children, two spiders (ka’kaw’wa)

pitted against each other on a coconut midrib held by the hand of the

players. The spiders engage each other

until one falls off the coconut midrib. The

spider who falls from the coconut midrib is the looser while the one that

remained is the winner.

Ka’kaw’wa

(spider)

Out in the “pa-yo”(rice fields), children would gather fish, shells,

crustaceans and other edible things. “Tuwali” folks call this “mang’dut”. The gathered things are placed in a bamboo

node container called “al-la-win” tied around the hip of the gatherer. A hand

held fish trap called “kat-tad” is used by early Ifugaos to catch mud fish

(dolog). The “kat-tad” has opened ends,

however the base (approx 2 ft in diameter) is larger than the top (approx

1.75 ft in diameter). It is made up of bamboo strips fastened by

rattan cords on bamboo rings, one in the base, middle and on the top. The “kat’tad” is carried by one hand and

placed down in the paddy floor at random.

When the “kat’tad” has a catch, the stunned fish will bump the walls giving

a jerking sensation, thus implying a catch.

With one hand, the fish is caught

and brought out through the top end.

Kat’tad

ma’ngat’tad

Another fish trap endemic to early Ifugaos is the “gu’bu”. It is made up of spited bamboo and fastened

up by rattan strips. It is cylindrical

in shape and more or less feet long. It

is about five to six inches to one foot in diameter depending on the maker. It has an opened end secured with a bamboo

node which allows the catch to be removed.

It has a small round opening not bigger than an inch. Pointed bamboo strips are positioned inward

in the opening to prevent catch fishes from getting out. “Bu-bud” or refuse from the fermented rice

in making rice wine (ba’ya) is placed inside the fish trap as bait. It is submerged in the rice paddies with the

open end a few centimeters above the mud.

The “gu’bu” is intended for the “yu’yu” (tuwali)

Gu’bu

Gu’bu

Another method of catching the “yu’yu”

is by the use of the “dol’ak” (tuwali) or particular vines and tree barks that

forces out the stunned “yu’yu” to surface.

Said vines and barks are taken in the forest, beaten to pulp and

submerged in water opening that goes into the intended field. Water carries the sap of the vine into the

entire field. As soon as the “yu’yu”

surfaces, it is gathered. Entry of

additional fresh water would dilute the water to enable the stunned fish to

recover. The vine is not toxic to

human.

Rivers, lakes, and other bodies of water are other places where children

learn basic native crafts.

“Mun-halop” is a “tuwali” word signifying a method of catching fish in brooks

and rivers using the method used in the rice field “gu’bu”. The

opening of the trap however is placed towards the flow of the water. The targeted fish is the small “ug’ga’diw”

(less than an inch long) which has the nature of following the water

upstream. The fish trap is basically made up bamboo

nodes. Splits are made on one end making

it possible to be expanded like a funnel by use of rattan twines. The other open end is the base which is

secured by another bamboo node which could be removed when getting the

catch. The size and length varies

depending on where the fish trap is emplaced.

This trap is also emplaced against the flow of water on dikes and

brooks. Fishes crabs and crustaceans

that go with the flow of water are caught in the trap. “Ma’mun’wit” is catching fish through the use

of fish hooks and line. The earthworm

and frogs are used as bait on this method.

Fresh water crabs is the main ingredient In the “bi’nayu an pu’hun di ba’lat”,

one of the native delicacy of earlier folks.

The freshwater crabs are wrapped in banana leaves and left to ferment

for three days. By the time the crabs

are brought out, it has a disagreeable odor.

Needless, the hard shell is removed.

The softer and crunchy parts are mixed in prepared banana blossoms through

pounding on native mortar (lu’hung) until it turns into paste. Catching fresh water crabs is a pastime for

children. The crabs are caught either with bare hands in crevices of the rocks

or catching them at night as these nocturnal crustaceans come out from their

hiding places. Early folks uses torch

made up of dried bamboo or reeds.

As soon as a boy could buckle up a bolo, joins his elders trekking the

wilderness. On these occasions, basic native

skills are taught by the elders. In a short while, children being familiar with

the terrain, go on by themselves, basically to gather firewood (ma’nga’iw) and to

gather edible plants to be served as side dish.

Balang’bang fruit

With the aid of small but tenacious native dogs, boys go in groups to

hunt in the forest. Tuwali folks call

this “mun-a’nup” or basically hunting.

The dogs finding their prey, corner them in tree tops or areas where the

game cannot escape until the hunter arrives and finishes or catches the game. Hunting basically encompasses learning the techniques of laying traps for

birds and small animals. “Mun-hu’lu” is

using the “u’-nut” which is the sturdy black fibers taken from a palm that have

natural beautiful trimmed leaves. The

black fibers are made into a loop that catches an unsuspecting bird that goes

into the trap. The “hu’lu” is placed

strategically on birds’ trails (ho’bang).

It is also used to trap the monitor lizard (ban’niya) squirrels

(amu’nin) and other smaller games, although the material used for the tap is

the “u’-we” or customized rattan thongs.

Another type of bird trap using the “u’nut” is the “ka’tig”. It is a series of loops arranged up in a tree

branch where an unsuspecting birds is trapped when it lands to feed on

fruits. The “ap’pad” and “li’ngon” are

also bird traps using bent bamboo or tree branches that spring up when

triggered by an unsuspecting bird.

While the two traps are same in principle, the “ap’pad” is laid on the ground while the “li’ngon” is

constructed above the ground. Using the

bird lime (pu’kot) is another method of catching birds. The birdlime is made from the sap of endemic

trees like the “pa-kak” (bread fruit), alimit, to’bak and many other sap

producing trees. By making a cut on the

bark, the sap flows out into a bamboo node prepared for the purpose. The gathered sap is heated until it reaches

the correct viscosity. It is placed on

twigs where an unsuspecting bird that lands is caught. The “liyok” or winged termite is used as the

bait. Early folks use the “bi’tu” to

catch larger game like the boar or the deer.

A “bi’tu” is basically a hole dug on the ground, covered and

camouflaged. An unsuspecting animal that

passes on the trap falls into the hole.

Sharp bamboo spikes or “hu-ga” in the Tuwali dialect are planted in the

hole to further immobilize the catch.

Ifugao folks gather the “al-laga” or edible red ants that build their

homes up in the tree tops for food.

Ifugao Amu’nin

Ifugao Amu’nin

The “lat’tik” or “pal’si’it” in the “Iocano dialect”

(sling shot) came about. This is no less

than a strip of rubber fixed to a Y-shaped branch and customized leather

scavenged from worn out shoes that serves as the pouch for the projectile. Small stones, preferably smooth and round

ones, are used as projectiles. Holding

the Y-frame with one hand and stretching the rubber strip with another with a

stone in the pouch and releasing it to a target, makes the “lat’tik” a potent

toy. The “lat’tik” which is normally found

looped around children’s neck is a handy tool for hunting.

Lat’tik

“Ahi-ani” or harvest

season in the “tuwali” dialect is the season when the palay is harvested. This season usually takes place every June to

July.

Ahi a’ni (harvest)

Ahi a’ni (harvest)

Ga’mu’lang

Harvested Palay Sheaf

(nab’tok an Pa’ge)

Mun ba’ta’wil

Mun ba’ta’wil

Customary Ho’nga’n

di Pa’ge Ritual during harvest season

Ti’ngab containing the bu’ga (black stones) nd pa’lipal (bamboo clapper

as paraphernalia for the bu’lul

Ti’ngab containing the bu’ga (black stones) nd pa’lipal (bamboo clapper

as paraphernalia for the bu’lul

Bu’lul – Ifugao granary deity

Bu’lul – Ifugao granary deity

As part of the preparation “Tuwali” farmers

prepare the “botok” or bundling cord for the “pa-ge” (harvested “palay”

sheaf). The “pun-botok” (bundling

cord) is a specially prepared bamboo strips measuring approximately 1/4 of a

centimeter thick, a centimeter in width and about a foot in length or the

length of the inter-node suggests the length of the bundling cord. The choice of material is the wild bamboo

variety called “a’no”. This wild bamboo variety

climbs up and dominates portions of the forest floor or forms a thicket on

brooks and small waterways. Choice stems

are gathered and cut by inter-node. It

is sliced lengthwise into four. The

inner soft part of the culm is removed.

The maker who is usually in a squatting position or sitting in a

“dalapong” (one-piece stool about six inches tall), firmly grasps one end while carefully

stripping the “botok” piece by piece with the use of a sharp knife. This taxing process is called “mangul’yun” in

the tuwali dialect. The maker occasionally shift his stripping on the other

side until what remains is a pentagon shape with a tail.

This is called the “pa’to”. Children would gather the “pa’to” and use it

as a dart in a competing thrown distance.

The “pa’to” is thrown by holding the end of the tail and spinning it

overhead or above the shoulder. It is

released forward with the tail acting as the balance.

Another variation of

this distance throwing game is the use of the “ug’gub”. The “ug’gub” is the young shoot of a

mountain reed (bila-u’). Before the “ug’gub”

is thrown, the player holds it by this fingers to where it balanced. Then bending back the elbow, jerks it

briskly forward releasing the dart. It

could also be thrown similar to the throwing of a spear.

The traditional “Bak-le” or rice festival, marks that the end of the

harvest season (ahi-ani) and the “kiwang” season is at hand.

Pounding the rice with the customary 3 pounders during the bakle fetival.

As women folks participate in the rice pounding

The customary bakle rituals

After the “tungo” (customary day

of idleness) is over, farmers start cleaning the rice fields for vegetable

plating. Weeds, grasses and rice stalks that are left after the harvest are cut

and piled in a mound in the watered rice field. Tuwali folks call this “ping-kol”. The

mound is about two feet high and more or less two feet in diameter to be

planted with variety of vegetables. During earlier times, no organic fertilizer

or insecticide of any kind is used on the planted vegetable.

Only in

Ifugao – the traditional Ping’kol

It is at this time of season that children mimic the primary chores of a

farming village - playing with

miniature rice fields. With bare hands,

children carve out from the mud miniature rice fields. Plants, tadpoles and other aquatic creatures

are gathered and added to the miniature rice fields. When the children are tired of playing with

their play rice fields, later inundate it.

Amid cheering and jests, children watch how the water released from a

nearby body of water utterly wash out their miniature play things. It is from this type of children’s merriment that

is told in a portion of the “bukad di tumitib”.

American writer Roy F Barton translated a part of the “baki” on one of

his books relating how “Ballitok, son of Ma’I’ngit from the “kabun’yan” (sky

world), played “miniature rice fields” with the sons of Ambalit’tayon.

The rice fields become shining

crystals with scattered dots in a distance.

It is during this season in the rice cultivation cycle that children have

the chance of playing in the vast

terraced rice fields. From the endemic

bamboo, children would made variety of toys.

The “pug’ik”. This native toy is made up from the bamboo variety

called “u’go”. That particular bamboo

variety has thin stem walls. Choice materials for this toy are internodes

which is about two to three inches in diameter. From the prepared inter

node, one of the end is open but leaving the other end with its diaphragm

intact. With the use of s sharp pointed

knife, a small hole is carefully bored in the center of the diaphragm. A stick which is about 5 inches longer than

the prepared bamboo inter-node is made. Stripes of old clothes or soft

tree barks are secured in the end of the

stick which is fitted into the open end of the toy. The toy is submerged

in the water to enable the strips of clothes be saturated with water enabling

it to fit snugly inside the inter node. When the closed end of toy is

dipped in the water and the stick pulled back, it siphons water. The toy

is raised up, pushing the stick forward thereby compressing the water.

Water gushes or sprout out from the hole reaching several meters forward.

“Naban’nu’uy in Imbungyaw”, is the scene of those unforgettable moments

of my childhood when we play the “pug’ik”. . We would run after one

another each with his “pug’ik” sprouting water at each other. We

would eventually wet ourselves playing with the native toy. At times we

would stumble and muddied ourselves but it would be one of the best days

we always look ahead”.

The “bul’did” is another toy that

traces its existence to earlier times.

It is equivalent to the present day modern dart. The toy is simply a bamboo node with open

ends. It has a diameter of approximately

one to 2 centimeters. The stem walls are

preferred to be thin. The projectile or bullet is loaded inside the toy and putting

the toy in between the lips, is blown vigorously to propel the bullet. Mongo

seeds are commonly used. Rice grains

could also be used, but have to be surreptitious to avoid being admonished.

With a bigger tube diameter, the “kabba’ung” fruit that looks like beads could

be used as projectiles. A child who expertly

plays with the “buldid” puts a handful of projectiles inside his mouth and with

the use of his tongue, manipulates the loading of the bullets inside the tube

and alternately blows into the tube to discharge the projectile. Depending on the weight of the projectile and

the force of the blow, it reaches several meters and at times could cause

injury.

\

The “buduk’kan” is another toy

invented by the early Ifugao children.

It is made up from the bamboo variety which has a small stem cavity

(approximately 1 – 2 cm) but with thick stem walls. There are two components for the toy. One is an inter-node about more or less a

foot long. The diaphragms are removed to

make the cavity open from end to end.

The other component is a shorter inter-node about four inches long with a

sturdy bamboo stick stuck on the stem cavity.

The stick should fit in the stem cavity; likewise, its length should be

shorter by an half an inch so that the second projectile would not be removed

when it is pushed forward. During earlier times, wild fruits and tender coffee

beans are used as projectile or sealant. When playing with the “buduk’kan”, the

first projectile that serves as the first sealant is fitted into the stem

cavity. Using the other component with

the stick, it is pushed forward to the far end of the toy. Another projectile or sealant is emplaced

like the first one. Pushing it further

would compress the air, thus producing the popping sound. The compressed air propels the first sealant

forward reaching several meters, the second sealant, taking place of the one

that was propelled. Another sealant is

fed inside the tube, hence, repeating the same process. With the availability of paper into the

highlands, children discovered that saturating the paper could also be used as

a sealant. The paper is made into shapes

and fitted into the stem cavity. Using

the component with the stick, the saturated paper is hammered to make a more

fitted sealant.

Buduk’kan

Tops

are spun in an axis while balancing in a point as it rotates in a

circular motion until the gyroscopic effect gradually lessen, finally

causing it to topple. The “pad-di-ing” is the earliest type of top played by Ifugao children. This indigenous top is made up from a spherical

or round shaped fruit about an inch in diameter and a bamboo stick about five inches long. One end of the bamboo stick is

sharpened. The fruit is pierced in the

center until the stick protrudes for about a few centimeters on the opposite

side. The protruding stick would serve

as the point of axis. The toy is spun by clasping the stick with both hands and

in a clock wise – counter-clockwise twisting motion, the toy is finally

released with momentum enabling it to spin on its own. The wild

“lab-labong” or an immature pomelo/orange (tabuyug) is choice fruits for this

toy.

Lab’la’bong tree and fruit

Lab’la’bong tree and fruit

The “Baw-wot” or native tops are endemic

to Ifugao children since earlier times. The native top is made from hard wood variety trees. It is

pear shaped and exceptionally with a conical base. A two inch nail is fitted

in the base leaving approximately half an inch protruding to serve as the axis.

The nail is sharpened to enable the top to spin smoothly (ma’di-ing). A

top with a blunt spin (mun-gal-ga-landok) spins into a pendulum and have s

shorter time in spinning compared to a top which has a sharpened nail (axis).

It is normally played by tightening a cord (alittan) around the body, starting

from the axis up. The other end of the

cord is looped in the player’s middle finger.

The conical tip of the toy should face up before throwing it and jerking

it momentarily as the top is about to disengage from the cord. While spinning on the ground, with the stroke

of the point finger and middle finger would let the spinning top hop on the

player’s palm. Tuwali children call this “tapay-ya-on” meaning letting the top

jump and continue spinning on the player’s palm. While the top is still

spinning, the player with a tilts of his palm and with a jerking motion smash

the spinning top to the group of tops placed inside the circle. Ifugao

children have an array of games using the native top. The most common is gathering all the tops in

the center of a drawn circle. The player

after lacing his top, smashes it into the gathered tops. While the top is in full spin, the player let

the top jump in his palm and smashes the spinning top to his target. Tops thrown out from the circle are returned

to be target in the next round of game.

Only the tops that had not been thrown out in the circle are removed to

join the player on deck. Prior to the

start of the game, players determine their sequence. This is done by targeting a dot drawn on the

ground. The distance of one’s top from the drawn dot manifests their

sequence in playing. Another variety of top game is using the string (alittan)

to loop the top. It is looped in such a

manner that it resembles a medieval flail with the nail pointed towards a right

angle. The player squats or kneels

facing the target, his strong hand holding

“alittan” from the desired length. With a calculated aim, smashes the top into

his target. The force would break and

splinter tops. Other tops that are made

of soft wood would break into two,

considering them losers. At the end of

the game, almost all tops are dilapidated, signaling the kids to start making

another new top. To enhance the color of

the top, it is buried beneath the decaying grass and mud in the rice field for

a couple of days to make it black. This method is called “inil-bog” in the

Tuwali dialect. This particular

toy is immortalized in one of the passages in the “baki” ritual, “bukad di

tumitib”. It is in this occasion that

Bal-lituk, son or Ma’ingit of the sky world and grandson of Amtalao of

Kiyyangan played tops with the children of Ambalittayon. In the “bukad’ (part of oral tradition in a

ritual), it relates how Amtalao gave to his grandson, “Bal’lituk” his top made

up from the core of a “galiw-giwon” tree and how Bal’lituk was too much (na’ma’hig)

to his opponents in the game of tops.

Mun’ba’baw’wot (game of tops)

Mun’ba’baw’wot (game of tops)

Early Ifugao practices

animism. They believe in the existence of

deities and numerous supernatural beings.

They also worship the spirit of their dead ancestors and departed loved

ones. This is done through the performance of

rituals by the “mun’baki” or native priests.

Aged old oral traditions of the Ifugaos called “baki” based from the

Ifugao Mythology are invoked in the ritual.

The chicken, pig or

water buffalo (carabao) are the common choice of animals to be offered

depending on the ritual to be performed.

The pig’s bladder is a priced material for a toy ball during earlier

times. Tuwali folks call it “kabu’ut”. After

the prognosis is announced, the carcass is chopped into pieces. A waiting child is nearby to claim the “kabu’ut”. Air is puffed immediately inside the “kabu’ut”. The opening is tied securely as to prevent

the air from escaping. After a few

minutes of air drying, comes a ball. This

ancient tradition, it is not only practiced by the ancient Greeks and Egyptians,

but the early Ifugaos as well.

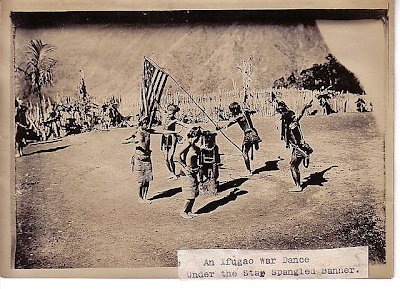

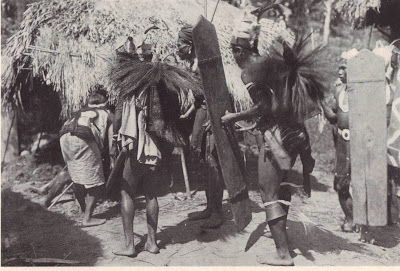

The Ifugaos are known as

one of the tenacious headhunters of Northern Luzon.

Head hunting victim

Another Head hunting victim

It was only through the governance by the

Americans in the Cordillera that the practice gradually came to an end.

A child by nature learns

the art of spearing which is basically the fatal blow before a head is severed

during head hunting expeditions. Spear

replica made up from reeds, shrubs and tree branches are thrown to a banana

stalk as an imaginary target. As a game,

children would take turn in throwing

his toy spear on the designated target.

The “upak di moma” (betel nut fronds) is another indigenous play thing among the

children. This particular part of the

areca palm, by nature disengages when it matures thereby giving new fronds to

replace the fallen one. When fresh, the sheathing base is soft and

smooth. A mature betel nut frond is normally a foot wide and about 3 to 4

feet in length. It is this fallen frond that the

children gather to be used as a toy in the “gigin-nuyud”. This word literally

comes from the word “guyud” meaning to pull. It is the leathery

soft portion of the frond where the rider compact himself by sitting and

putting his foot together and holding the stripe with both hands. The

other child, who is the puller, pulls the stripe forward and moves

around. At times, there could be two or more puller enabling the native

toy to be towed faster. Likewise, two to three small children could also

compact themselves inside the frond, grasping the other riders by the waist. Only the front

rider holds securely in the stripe.

There are instances when the toy would overturn as it hit a bulge in the

ground sending the riders tumbling on the ground or every player gets wet and

muddy when playing on a rainy day.

Mo’ma, dong’la in the rice fields

The “ak-kad” (hand held stilts) is another indigenous Ifugao toy. It is made from two straight poles of hard

wood variety trees. It is more or less

six feet in length depending on the user.

It is exceptionally bigger in the base (approx 2 – 3 inches in diameter)

and decreases gradually to the top. A

piece of wood is fixed securely at approximately two feet from the base. This serves as the foot support. Smaller children and beginners usually mount

from a platform to enable them to have an easier access to the foot support and

balance. When mounted, the stilter balances himself as he holds the upper

end of the pole while synchronizing his foot, hand and body movement.

Seasoned stilters can negotiate the rice paddy dikes and narrow trails without

much ado.

Early Ifugaos have their

own games of strength. “Bul’tung” or Ifugao native wrestling is primarily a

method of settling boundary disputes on adjacent rice fields and inherited

lands. In the course of the wrestling match, to where the victor

throws and immobilizes the looser would be the new boundary for the disputed

property. It

is however played by young boys and older men alike as a game of proving ones

prowess. This is played by two

opponents. The competitors wearing only the native g-string wrestles each other

until one is pinned and immobilized to the ground. Starting position on this game is holding

the opponent by the g-string. The

belligerents grapple each other until one falls and is immobilized.

“Hin’nukting” is derived from the

“tuwali” word “huk’ting” meaning to bump.

This game of strength is played by two or more players. The players bend one of

his legs towards the buttocks and holding it steadily by the arm. A right

bended leg must be held by the left hand or vice versa. The other free arm must

not dangle but must stay steady at the midriff area. It is however the option of the player

if he holds on to his g-string or shirt to enable his free arm not to

dangle. The player limps with his free leg and balances himself as he poised

forward to engage his opponents. This is

done by pushing or bumping using the shoulders and forearm. A player who

stumbles or falls looses and automatically leaves the arena. A player who loses his grip on the bended

legs is also a looser. The game

initially starts with several players unless it would be a matching game for

two players. On the course of the game,

players who stumble or loses his hold on his bended knees automatically leaves

the matching arena until only one player remains as the winner.

Hin’nuk’ting

Another version of the

“Hin’nukting” is played by players grouped by twos. One of the players straddles at the back of

his partner and wrap his arms just above the shoulder and stretches his legs

forward. The stretched legs are held by firmly and use it to bump and

knock down his opponents. A player looses the game if he stumbles or

fall, loses his hold on the straddled player or a straddled player loses his

hold on his partner.

Another variation of hin’nuk’ting

Sang’gul (arm wrestling)

is another game of strength. This particular sport is played by two players.

Each participant places one arm, either the right or left, on a surface. The player face his opponent with bent elbows

and touching the surface. One version of this sport is that the

competitors start the game by griping each other's hand. Another version

of this is that the participants engage his opponent by interlocking

the forearm. Upon the go signal of a referee, each participant puts

his force on the other until the arm of the opponent is pinned in the surface

with the winner's arm over the loser's arm.

“Dulhi” or middle finger wrestling is another game of

strength. This game is participated by

two individuals who engages his opponent by gripping each other’s middle finger

as the elbow is set on a flat surface. Upon the start signal, the

participants grip the middle finger of his opponent and put his force on the

other until the loser is pinned on the surface. The mechanics of this sport is

similar to the “sangul”.

Spanish rule in the

Philippines starts with the establishment of the first Spanish settlement in

Cebu by Lopez de Legazpi on 13 February 1565 and ended when Spain seceded her

colonies to America on 25 August 1898.

During the three century period rule of Spain in the Philippines, the

highlands of Ifugao remained free from foreign bondage even after the

establishment of the Spanish mission in Kiangan in 1892. In spite of the Spanish presence, the Ifugao

natives continued unhampered in their way of life, customs and traditions.

Mun’u’lut

Mun’ah’hud hi ba’yu (two

pounders)

No schools were

established during that era, with the exception of a few who are taught to read

and write by Spanish

missionaries Juan Villaverde and Julian Malumbres. In 1904, American soldiers introduced the

first formal learning classes in Kiangan.

Other

schools were opened in other areas of the Cordillera, such as this in Benguet.

With the Americans in

control not only the whole cordillera but Ifugao as well, travel to not only to

adjacent villages but to neighboring provinces was made safer.

As a result, new games

were introduced and borrowed. “Tag games” were introduced. This involves a player chasing other

players in an attempt to tag or touch them with the fingers. The one chasing the other players is called

“mang’-nge” in the “tuwali” children’s dialect.

It is equivalent to the “it” in the English language. The

players usually makes an elimination process who would be the “mang’-nge”,

otherwise the last player to join the group automatically becomes the

“it”. The player who is being chased, try to avoid the tag as it

would make him the next “mang’-nge” in the succeeding game. Other “Tag and

Touch” games have the “home base”. It is a pre-designated area, or a

prominent feature in the vicinity where the players are safe from being

tagged. The base could be a line or circle drawn to the ground. It

is also the place where a tagged player may outwit the “it” by running ahead to

the base after being tagged, thus making him free from being the next

“it”.

Inside “abung” (Ifugao Native

house), a child who is blindfolded with the use of old clothes, goes after his

playmates. The other children run about in the four cornered native house

to avoiding being tagged. With shirks and laughter, the “mang-nge” would

eventually be able to tag one of the playmates who will eventually be the “it”

in the succeeding game.

During the 1960’s, one would not

miss the massive rectangular granite table under the avocado trees fronting the

old Kiangan Central School building. It

is to the right, just after negotiating the stone stairs. The granite table, which is more or less two

meters long, a meter wide and a foot thick is placed atop two perpendicular

stone slabs. It is the favorite playpen

for children before the bell rings for children to line up for classes. Children would climb atop the stone table to

play their variation in the “tag game”.

The “it” or “mang-nge” would go under the stone table and emerge

suddenly on the left or right sides trying to tag the feet of anyone up in the

stone table. Children in the stone table

would shriek and laugh while moving to the safe area to avoid the tag. Some would fall as a result of the sudden

surge of the children on a corner. When

a “tag” is made, the one who was tagged gleefully replaces the “it” who joins

the other children atop the granite table.

The process goes on until the bell rings for classes or time for the

pupils to go home.

The “ball tag” is one of the

variations of “tag” games. It is another

popular game among children. It is basically called a “ball tag” since a

thrown ball is used to tag players. Two teams play this game, the

playing team and the opposing team. There is no limit in the number of

players. The playing team position

themselves inside of the playing field while the opposing team positions

themselves at the far ends of the playing field. The game starts when the tag ball is thrown to

the playing team. The players do their best in avoiding the thrown ball, otherwise,

will be obliged to leave the playing field when hit. As the thrown ball reaches the other end, the

playing team runs to the opposite side to maintain a safe distance from the

opposing team who will throw the tag ball at random. The game continues until all the players are

eliminated. This automatically makes the

opposing team the playing team and vice versa.

During summer, the playing ground is elaborately marked with charcoal or

at times a line is etched on the ground.

“Pin’nung’pung” is the traditional “hide and seek” children’s game in

English. It is a game wherein the players

conceal themselves in the environment, and to be found by the lone

"seeker" who is the “mang’nge”. The home base is usually a landmark

or prominent terrain feature. It is the place where the seeker starts the

game by leaning in the home base (wall, post, tree trunk) and burying his eyes

in the back of his palm while counting.

After counting some numbers, the “mang’nge” shouts in a warning, “umali’yak”

(I’m coming). The player (hider) who has

not concealed himself yet, answers, “in’dani” (just a moment). The “it” repeats, “umali’yak” , several times

and when no one answers, finally shouts, “umaliyak man mo” (I’m coming

now). The “it” leaves the home base and

goes about seeking for the concealed players.

The “seeker” shouts, “pung” affixing the name of the player who was

compromised and makes a dash to the home base, tagging it and shouting

“save”. The “seeker” continues looking for all the other players until everyone

is accounted. A “hider” who had been compromised could outwit the “it” by

running ahead and tagging the home base it before the “it” makes a tag. This special situation makes the “it” still

the “it” in the repletion of the game. The

only way to reverse the status of the “it” is to successfully locate all the

players and tagging the home base ahead before any player could make a

tag. In this situation, the first

“hider” to be compromised automatically becomes the “mang’nge” in the

succeeding game.

“Pi’pin’nal’lat’tug”

is a variation of the “hide and seek” game.

Children playing this game are divided into two groups, each with a

leader who selects the members. The players,

upon the start of the game, scamper to their respective “start” areas and blend

with the environment. Then move

cautiously towards the direction of the opposing team to locate and compromise them.

The player, who sees an an opposing player, shouts the traditional “pung” and

affixing the name of the one compromised (i.e. – pung, Dumayyahon). The one, who was compromised, automatically comes

out in the open and announces his status.

All players who are compromised proceeds to the base area. After everyone is accounted for, the

succeeding game starts with the swapping of start area. This game is played as a war game and in the

absence or scarcity of toy guns during earlier times, the children uses

indigenous native materials as replica, depending on the user’s imagination.

The banana plant or “ba’lat” in the

“tuwali” dialect is the largest herb flowering plant that grows 6 to 7.6 meters

tall depending on the variety. The banana produces a single bunch of fruit

and slowly decomposes after harvest. Several offshoots however grow from

the plant which replaces the former plant. It is through the resourcefulness of

early natives by diverting the flow of water with the use of the banana stem

sheaths to make instant water showers.

This is called the “tud’de in the “tuwali” dialect. Through the

ingenuity of children, variety of play things is made from the fallen banana

trunk. The “bal’bal’le” (play house) is

primarily made up from materials taken from the banana. After the basic structure of a play house is

made in place, banana stem sheaths are laid for

the roof. Inter-lapping the stem

sheaths enables the roof to be resistant from the rain and sunlight. Another

set of banana sheaths are placed for the walls. Covering the ground with

banana leaves makes a perfect cool play pen where children spend the rest of

the day cooking and playing. Banana leaves could also be used

for the roofing and walls of a play house.

The children organized themselves as members of the family such

as father, mother and children.

Customarily, the eldest boy and girl shall act as the father and mother

respectively. Younger children represent other members of the family and

are sent for errands. Food, water and other necessities are normally foraged

from homes of the players. Cooking food and other house chores are mimicked

inside the playhouse. The frolic of playing “bal-bal-le” would at times

last until dusk until parents come looking for the children. From the banana core (bu’ngol), children

will fashion the body of a four wheel vehicle. The round banana core is cut diagonally for

the wheels while the axle is made up from reeds or twigs. It is fastened on the body by twigs. When everything is ready, a twine is tied

securely on the toy truck. Children

would line up, each towing his toy.

Round and round in the neighborhood, the toy trucks would be towed,

unmindful of the time passage.

A rubber band is made up from rubber and latex. It comes in the shape of a loop and in

different colors. It is typically used to bind objects. With the

appearance of the rubber band in the high lands, children used it in varieties games. Tuwali children call it “kal’lat”. Under the Ifugao native house (da’ulon),

children would play “ti’tin’nuduk hi kal’lat”.

“Ti’tin’nuduk” literally comes from the borrowed Ilocano word “tu’duk”

meaning to penetrate or pierce an object.

It is synonymous to the “tuwali” word “tu’wik” but the game was never

called “tu’tu’wik”. With an equal amount

of rubber band from each participant, one of the players, burry it inside the

dust or soil gathered into a mound.

Then one after the other, each player, with the use of a coconut midrib

or “ba’ing, pierces or penetrates the mound for the hidden rubber band. Rubber bands that are caught by the midrib

are won by the player. Other rubber

bands that have been uncovered are hidden back into the mound before the

succeeding player takes his turn. The piercing or penetrating of the mound for

the hidden rubber band goes on until all the rubber bands are won. The game continues until most of the rubber

band are won or until one of the players lost all his rubber band in the game

of “ti’tin’nu’duk”.

“Pin-nuk-puk” is another children’s

game using the rubber band. It comes

from the borrowed Ilocano word “puk’puk” meaning to beat on a platform. Two players would sit by the floor or bench

and move two rubber bands towards each other by beating alternately their

closed palm on the flat surface where the rubber bands are placed. As a result, air emanated from the closed

palm moving the rubber band forward. A player wins over the other

when he successfully over lapped his rubber band on his opponent’s rubber

band.

Hin-nap-ud comes from the “Tuwali”

word “hap-ud” meaning to blow. Two players lay in prone position facing

each other on a flat surface, preferably in the wooden floor. Their respective rubber bands placed a few

inches away from the mouth. Taking

turns, each player blows vigorously on the rubber band enabling it to move

forward. The player wins when he

successfully over lapped his rubber bahnd on his opponent’s rubber band.

Each player contributes an equal

number of rubber band. The

collected rubber band is randomly divided into two parts and then are looped

together. Using their foot, the players

take turns in unloosing the rubber bands. A player could stomp, kick or make any foot

movement that could unloose the rubber bands.

Rubber bands that separate individually from the looped are won by the

player. Rubber bands that had separated

from the loop but still connected are not considered won. The game of untying the looped rubber band

continues until all the rubber bands placed on the bet are won. Children possessing several rubber bands,

loop it to make a chain like figure.

A marble is a small spherical toy

made from glass. It is about ½

inches in diameter and comes in strange combination of swirling colors

inside. Ifugao children call it “bulintik” or

“holen” corrupted from the non-Ifugao word “jolens”. It is traditionally

used in variety of games. Basically, it

is played by knocking the other players’ marble by holding it between

the bent index finger and the knuckle of the thumb. Then with a calculated aim,

flips it towards the target by the straightening action of the thumb.

One of the common marble games

starts from a line etched in the ground as the starting point. Four small holes of approximately 2 - 3

centimeters wide and a centimeter deep are dug in the ground after the drawn

line. The distances of each hole is

measured by a player connecting the left and right foot, then marking the spot

for the hole. To determine their order

of succession in the game, the players flip their marbles one at a time on the

first hole. The nearest to the hole or

the one who shoots his marble into the hole automatically becomes the first player

followed in succession based on the distances of marbles. A tie is broken by repeating the process;

however the rematch would be vying for the sequence which the two had a tie,

the other placed ahead before the looser.

From the starting line, the first

player flips his marble on the first hole and continues the course until he failed

to shoot his marble in the targeted hole.

This is the only time the next player starts or continues his course. As a rule, the players arriving at the

fourth hole, reverses towards the third, second and first hole. In the course of the game, a player after

making a successful shoot can hit other marbles of his choice. In this process, marbles that are hit are

obliged to start again on the first hole.

Every hit is equivalent to a shoot; hence a player who is the second

hole shall omit the third hole in the process.

That player would proceeds to the fourth hole as his next target. A player who has two hits would be exempted

for two successive holes. The player who completes shooting his marble on all

the holes is the winner. The elimination

of the players as winners continues until only one player is left – the one who

is unable to complete the course and now the looser. The looser shall be punished by every player.

The common punishment is to let all winners

hit the loser’s marble while the latter positions his marble in every hole after

a successful hit. What is taxing is that

the looser goes after his marble which is propelled in a distance after a

hit. Other punishment includes hitting

the clenched fist of the looser with a marble flipped by the winners.

Another variation starts by each

player putting equal amount of marbles in the center of the drawn circle. From the drawn line, players take turns in

knuckling out the marbles out from the circle.

A marble thrown out from the circle is considered a win. Marbles that remain inside the circle are

targets for players. The game continues

until all the marbles are won.

“Kandiling” is another popular game for children. This game is predominantly played by girls. It is an ancient game, each geographical place

have a native name for it. It is similar

to the English “hopscotch”. It is a

game played in a course through a pattern drawn or etched on the ground. The pattern is divided into several

geometrical figures. Players use aiming

markers, usually a small flat object such as stones or pebbles, in playing the

game. Starting the game, the players

aim their markers in a line drawn in a distance to determine the sequence of

players. The player whose marker touches

the line or closest to the line is the first player. The one farthest from the line automatically

becomes the last player. Players hitting

the same mark or distance from the drawn line will have to compete again to

break the tie. The first player tosses

her marker into the first square and continues traversing the course unless a

rule is violated. It involves hopping,

straddling moving the marker in the pattern using the foot. Other players, who are always on the lookout

for violations, caution the player to stop if a rule is violated. Common rules that apply to the game are: the marker should land inside the targeted

pattern without touching the lines and it should not bounce out from the

pattern. A player should not step in

any drawn line or traverses outside the pattern. In a certain sequence of the course, the player looks up denying the visual guide

on the pattern. A player who completes

the course is entitled to throw her marker in the pattern. She marks the pattern where her marker falls. The player who has more marked pattern is the

winner.

“Shiatong” is a game since ancient times. In the course of time, this game found its

way into the hinterlands of present day Ifugao. This game is played by teams or

individual players. Two sticks are

required in this game. A stick which is

more or less a foot long and a shorter one approximately 4 to 6 inches long. An

elongated hole, about two inches wide, three to four inches long and two inches

deep is dug in the ground. This serves

as the base. The base player is the

player who is in the vicinity of the base hole doing the courses of the

game. The opposing players are the rest

of the players who position themselves a few meters away facing the base. The opposing players are on the guard trying

to catch or hit the shorter stick propelled by the base player. There are basic rules for the changing of the

base player: one; If the propelled stick in any stage of the

game is hit by the opposing players, two; if the horizontally laid stick on the

base hole is hit by the shorter stick thrown by the opposing players and three;

if the base player misses to hit his shorter stick in any stage. In this case, the shorter stick will just fall

in front of the player instead of propelling forward. Before starting the game,

the players determine their sequence.

One at a time, each player puts the shorter stick in an angle inside the

elongated hole. The other end of the

stick must be protruding. Using the

longer stick, the player hits the end of the shorter stick. The inertia makes the

stick leaps into the air. The action of

the player must be instantaneous as he must hit it while it is in midair. The short stick must be propelled in a

distance to have a score. Using the longer stick, the player measures the

distance from the point where the short stick is up to the base hole. The player who will have the most number of

measurements automatically becomes the first player. Relatively, this is how the third stage of

the game is played.

Starting the game (stage one), the base player positions

himself near the elongated hole. Then

arranges his shorter stick horizontally over the hole. Bending low, and in a wedging motion,

propels it forward to the direction of the opposing players. The other players try to catch or hit the

propelled stick. If the short stick is

hit or caught, changing of base player rules apply. However, if it was not caught or hit, the

shorter stick is picked up and thrown back targeting the shorter stick was laid

horizontally over the base hole. If the

shorter stick is hit, changing of base player applies. If it is not, the base player proceeds with

stage two. The base player picks up the

shorter stick. Holding it by the edge

(either horizontally or vertically) and hitting it to propel forward. Rule of the game apply. If the shorter stick is not caught or hit,

the base player stands on guard near the base hole holding the longer stick

ready to hit back the short stick which will be thrown back by the opposing

players. If the base player misses the

thrown stick and the stick fell near the base hole, changing of base player

applies. This is so especially if the

short stick fell near the elongated hole and the distance is too near to make a

measurement for a score. However, if the

stick fell further away enabling the base player to measure a score, he

continues to stage three. This is

practically a good score for the player if he was able to hit thrown stick in

midair and propelled it further away to enabling to make a measure for the score. Stage three is described in the mode of

determining the players’ sequence in the game.

A player who finishes the stages of the game is not a win yet. Individual scores is the factor in winning

this game. It however depends on the

agreement of the players for one of them the reach an agreed score before all

scores are tabulated. The player who

garnered the most score is the winner while the least automatically is the

looser. As punishment for the looser,

the short stick is propelled forward as in stage two by the winner(s). The looser would then pick up the stick and

run towards the base shouting “shaaaaa” continuously without interruption. Arriving at the base hole, the looser would

then briefly add “tong” while briskly putting down the stick to the hole, thus culminating

the punishment. While serving the

punishment, the punished player should inhale then controls the exhalation of

his breath while shouting “shaaaa” to enable one not to be out of breath before

completion of the punishment. A stoppage

in the word “shaaa” is noticeable since the player will have to pause to

inhale. At this point the player being

punished would stop where his shout is interrupted. The winner would again

propel the stick forward as in Stage two.

The loosing player is obliged to repeat the punishment until he

completes the punishment without interruption on the word “shaaa” which he

shouts while running towards the base hole.

Then reaching the base hole, the punished shouts “tong”, completing the

word “shatong”, while simultaneously shooting the short stick into the base

hole.

Today, most of the ethnic games in Ifugao are either

a thing of the past or games rarely played.

The “kabu’ut”, “gi’gin’nuyud” using the betel nut frond (u’pak di mo’ma),

children practicing spear throwing in a banana trunk or fern tree

(kati’bang’lan), pug’ik, buduk’kan, bul’did and many other games are not played

any more. Hunting as a sport or pastime using

the spear is now obsolete. The sling

shot or “lat’tik” came in as a substitute weapon for hunting but is now

replaced by the present day compressed air rifles which are now the fad of

hunters aside from small caliber firearms which are commonly used. Other traditions such as the “mang’dut” or

gathering shells and crustaceans in an open rice field are dwindling. The “dol’ak” was replaced by the potent and

destructive insecticides. This

contributed to the rapid destruction of the environment. Several plants that grow abundantly in the

rice fields, fishes, crustaceans and birds became endangered or were never seen

again. An example is the beautiful

colored bird called “ti’wad” that only appear during the season of “kiwang” and

“ahi’tu’nod (planting season). Just like

the old Ifugao “talindak” that is worn by farmers to protect themselves from

rain, would be a miracle if you see it today.

Talin’dak (equivalent to the

present day poncho

And before I reached my teens, the “yakayak” which

is used by earlier folks to catch fish, tadpoles and other freshwater edibles

was already extinct.

Ya’ka’yak

Thanks to the early Americans who built schools thus

introducing literacy to in Ifugao. This

was followed by Early Belgian Missionaries.

Today, present day games such as basketball, volleyball and others games

are played in schools and communities. With

the availability of video games in the high lands of Ifugao, it

is virtually everywhere, from homes, arcades, and school. It is a fact that

computer game, particularly those that involves violence gives a negative

influence to the growing child. Unlike

the old traditional games that promotes family and community ties. Moreover, it gives a positive influence to

the development of a growing child.

Whatever the future game be, the Ifugao children is prepared to adopt

and be a part of it.

My thanks to the various Ifugao cyber forums with whom I copied

the pictures

Malpao, Kiangan, Ifugao

16 February 2013